Shunting The Current When Spot Welding

Figure 1 - The steel between the copper-based electrode tips creates enough resistance to the current flow to make a fusion weld.

Figure 1 - The steel between the copper-based electrode tips creates enough resistance to the current flow to make a fusion weld. The squeeze-type resistance spot welding (STRSW) process sometimes requires initial help in the form of shunting the current flow. If you have ever used STRSW equipment for repairs you have likely done some shunting, either knowingly or not. A sound spot welding repair requires being aware of when shunting the current is taking place and how to shunt properly.

STRSW Process

To understand how shunting works and why it is sometimes necessary, consider how a resistance spot weld is made. A short burst of current flows between the electrode tips when the spot weld trigger is pressed. The nature of current is to flow through the path of least resistance. If there is a conductive surface between the copper-based electrode tips, such as bare steel, that is the path of least resistance. But since steel is not as good of a conductor as the copper electrode tips, there is resistance to the current flow, enough resistance to heat the steel to a molten state. Pressure applied to the electrode tips both before and after the short burst of current helps contain the molten steel to that spot.

Shunting Coated Steel

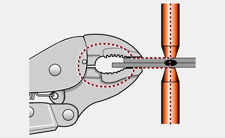

Figure 2 - When shunting, current flows through the shunting clamp first, but most of the current flows between the electrode tips.

Figure 2 - When shunting, current flows through the shunting clamp first, but most of the current flows between the electrode tips.

Conductive coatings on the steel, such as zinc or weld-through primer, increase the resistance but still allow a spot weld to be made. Nonconductive coatings do not allow a weld to be made. The most common of these is E-coat, the factory corrosion-resistant primer applied to every original and replacement body panel.

Most of the E-coat on the mating surfaces can be preserved when replacing a part with STRSW through the use of a shunting clamp. The E-coat only has to be removed on the outside surfaces. The shunting clamp is positioned at the first weld site and the first spot weld is made at the adjacent site (see Figure 2).

When the spot weld trigger is pressed, current flows from one electrode tip. When the current meets the nonconductive coating at the mating surface, it looks for the nearest conductive path which is through the top workpiece, around the shunting clamp, and back through the other electrode tip. The E-coat at the mating surfaces burns away. This is all happening very quickly. In fact, the majority of the current, in the short burst of current, travels between the electrode tips. The detour through the shunting clamp was only a brief, but necessary, diversion.

Figure 3 - Any other fit-up clamps should be insulated with tape to prevent unintentional shunting.

Figure 3 - Any other fit-up clamps should be insulated with tape to prevent unintentional shunting.

Note that the E-coat does not have to be removed between the spot weld sites on the exterior of the flange. The current traveling through the coated workpiece is like current traveling through a wire coated with insulation.

Successive welds should not require a shunt. The previous spot weld serves as the initial conductive path. In fact, any other clamps used for joint fit-up should have the jaws wrapped in tape for insulation (see Figure 3). A shunt is again required when another series of spot welds are started.

Shunting with Weld Bonding

Figure 4 - This dedicated shunting clamp has a thick, stranded copper wire attached to copper clamping pads to allow easy current flow.

Figure 4 - This dedicated shunting clamp has a thick, stranded copper wire attached to copper clamping pads to allow easy current flow.

Weld bonding is resistance spot welds made through adhesive on the same flange. The process requires removing all coatings from the mating flanges, including the zinc coating, but the recommended repair adhesive is not conductive so shunting is required. The bond line is thin, but thicker than E-coat so a clamp specially designed for shunting is usually recommended. This specialty clamp has a thick, stranded copper wire connected to copper pads for a much better conductive path than regular locking pliers (see Figure 4). In fact, using this dedicated shunting clamp is a good idea when doing any shunting. With locking pliers, there’s a good chance some of the current will be lost at the pivoting rivet.

Shunting Alternative

Of course a shunt is not needed for any of these conditions if the E-coat on the mating surfaces is removed, or if the adhesive is left off the part of the flange where the first spot weld can be made. The concern at that spot is corrosion protection, but seam sealers and paint coatings will help keep the moisture out. The zinc coating can be left on the spot without adhesive when weld bonding. The uncoated spot doesn’t have to be at the beginning of the flange, but you wouldn’t want it at a location such as the bottom of the B-pillar where road splash may be an issue.

Using the first spot weld as the shunt is the preferred method when weld bonding three or more panels, such as when attaching an outer panel to a two-piece inner. There is another recommendation that will ensure conductivity between the panels in this worst-case scenario. The recommendation is to make an initial spot weld on the two inner panels. Leave the adhesive off that spot on the outer panel, and when the outer panel is attached, make another spot weld on top of the first spot weld.

Conclusion

With the STRSW process, shunting of the current is required for the first weld when there is a nonconductive coating or adhesive on the mating flanges. Other clamps used for fit-up should be insulated to prevent any unwanted current shunting. When weld bonding, a dedicated shunting clamp should be used for the best weld performance.

This article first appeared in the May 14, 2007 edition of the I-CAR Advantage Online.

Additional I-CAR Collision Repair News you may find helpful:

Related I-CAR Courses

Article validated in 2025

-

Toyota/Lexus/Scion Position Statement: Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning

Thursday, 28 July 2016

As the industry continues to ask if pre- and post-repair system scanning is necessary, Toyota/Lexus/Scion provides their answer.

-

Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning Statements

Wednesday, 9 January 2019

Are you wondering if a particular OEM or organization has a published statement on pre-repair and post-repair scanning? We have compiled a list of most of the statements on the subject, so you can...

-

ADAS, Calibration, And Scanning Article Hotspot

Monday, 14 January 2019

Since advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), scanning, and calibration first started becoming relevant, members of the collision repair industry have required as much knowledge as possible on...

-

BMW Position Statement: Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning - UPDATE

Friday, 10 April 2020

BMW has released a position statement related to pre- and post-repair system scanning. The statement applies to All vehicles equipped with on board diagnostics II (OBD II).

-

Honda/Acura Position Statement: Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning - UPDATE

Wednesday, 22 May 2019

Honda /Acura has updated their position statement on pre- and post-repair scanning to give more clarification on what is expected for scanning.

-

Quickly Identifying Outer Quarter Panels w/Rolled Hem Flanges

Monday, 5 March 2018

The I-CAR best practice article, Recycled Outer Quarter Panels w/Rolled Hem Flanges has gotten a lot of interest from the collision repair industry. It’s important to know which vehicles are...

-

General Motors Position Statement: Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning

Friday, 21 October 2016

As the industry continues to ask, are pre- and post-repair scans necessary, General Motors provides their answer.

-

Restraints Wiring Repairs

Monday, 23 May 2016

Over the past few months, we've been sharing OEM position statements on restraints wiring repairs. Now we're bringing them all together in one place for easy reference.

-

FCA/Stellantis Position Statement: Pre- and Post-Repair System Scanning

Thursday, 9 June 2016

FCA/Stellantis has released a position statement related to pre- and post-repair system scanning.

-

Typical Calibration Requirements For Forward Radar Sensors

Wednesday, 12 October 2016

Technicians should be aware of what’s required to keep advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) running safely after a collision. Whether that be aiming a camera, which can cause a system to not...

-

SEMA 2025: EV Collision Solutions

Thursday, 5 March 2026

I-CAR had numerous presentations at the 2025 SEMA show. One of the presentations focuses on Midtronics high-voltage (HV) safety solutions.

-

I-CAR Repairers Realm: FCA/Stellantis Corrosion Protection Updates - Coming Soon

Wednesday, 4 March 2026

I-CAR is having a discussion on FCA/Stellantis corrosion protection updates.

-

Bumper Cover Repair With ADAS: Mazda - UPDATE

Tuesday, 3 March 2026

A simple bumper repair on a modern vehicle may not be as simple as it seems. New technologies like blind spot monitoring, adaptive cruise control, and other advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS)...

-

I-CAR Just In Time: Torque Wrench Use

Friday, 27 February 2026

Sometimes seeing is understanding, that’s why I-CAR's technical team created the Just in Time video series to guide you through a variety of collision repair topics from ADAS and EVs to repair tips...

-

I-CAR Repairers Realm: I-CAR Registered Apprenticeship Program - Now Available

Thursday, 26 February 2026

I-CAR had a discussion on the I-CAR Registered Apprentice Program (RAP).

-

Bumper Cover Repair With ADAS: FCA/Stellantis

Wednesday, 25 February 2026

A simple bumper repair on a modern vehicle may not be as simple as it seems. New technologies like blind spot monitoring, adaptive cruise control, and other advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS)...

-

I-CAR Just In Time: Digital Tram Gauge Basics And Steering Column Measurement Tips

Thursday, 19 February 2026

Sometimes seeing is understanding, that’s why I-CAR's technical team created the Just in Time video series to guide you through a variety of collision repair topics from ADAS and EVs to repair tips...

-

GM Repair Insights: Fall 2025

Tuesday, 17 February 2026

The fall edition of General Motors (GM) Repair Insights magazine is now available.

-

GM Repair Insights: Winter 2026

Tuesday, 17 February 2026

The winter edition of General Motors (GM) Repair Insights magazine is now available.

-

SEMA 2025: Three-Dimensional Measuring Presentations

Thursday, 12 February 2026

I-CAR had numerous presentations at the 2025 SEMA show. Two presentations featured information about three-dimensional measuring of vehicles.

- 2026

- March 2026 (3)

- February 2026 (11)

- January 2026 (11)

- 2025

- December 2025 (8)

- November 2025 (11)

- October 2025 (13)

- September 2025 (11)

- August 2025 (12)

- July 2025 (11)

- June 2025 (11)

- May 2025 (11)

- April 2025 (13)

- March 2025 (12)

- February 2025 (11)

- January 2025 (12)

- 2024

- December 2024 (8)

- November 2024 (10)

- October 2024 (13)

- September 2024 (10)

- August 2024 (12)

- July 2024 (11)

- June 2024 (9)

- May 2024 (13)

- April 2024 (12)

- March 2024 (12)

- February 2024 (12)

- January 2024 (9)

- 2023

- December 2023 (8)

- November 2023 (12)

- October 2023 (11)

- September 2023 (11)

- August 2023 (12)

- July 2023 (9)

- June 2023 (11)

- May 2023 (12)

- April 2023 (11)

- March 2023 (12)

- February 2023 (10)

- January 2023 (11)

- 2022

- December 2022 (11)

- November 2022 (12)

- October 2022 (11)

- September 2022 (13)

- August 2022 (11)

- July 2022 (10)

- June 2022 (13)

- May 2022 (11)

- April 2022 (12)

- March 2022 (10)

- February 2022 (11)

- January 2022 (13)

- 2021

- December 2021 (13)

- November 2021 (11)

- October 2021 (13)

- September 2021 (14)

- August 2021 (12)

- July 2021 (15)

- June 2021 (17)

- May 2021 (11)

- April 2021 (14)

- March 2021 (20)

- February 2021 (14)

- January 2021 (14)

- 2020

- December 2020 (13)

- November 2020 (17)

- October 2020 (12)

- September 2020 (14)

- August 2020 (11)

- July 2020 (18)

- June 2020 (14)

- May 2020 (14)

- April 2020 (19)

- March 2020 (12)

- February 2020 (13)

- January 2020 (14)

- 2019

- December 2019 (13)

- November 2019 (19)

- October 2019 (25)

- September 2019 (20)

- August 2019 (22)

- July 2019 (22)

- June 2019 (20)

- May 2019 (19)

- April 2019 (20)

- March 2019 (20)

- February 2019 (18)

- January 2019 (17)

- 2018

- December 2018 (18)

- November 2018 (19)

- October 2018 (17)

- September 2018 (16)

- August 2018 (21)

- July 2018 (20)

- June 2018 (21)

- May 2018 (16)

- April 2018 (19)

- March 2018 (21)

- February 2018 (15)

- January 2018 (20)

- 2017

- December 2017 (13)

- November 2017 (15)

- October 2017 (19)

- September 2017 (20)

- August 2017 (19)

- July 2017 (18)

- June 2017 (19)

- May 2017 (18)

- April 2017 (13)

- March 2017 (18)

- February 2017 (10)

- January 2017 (11)

- 2016

- December 2016 (9)

- November 2016 (14)

- October 2016 (21)

- September 2016 (10)

- August 2016 (11)

- July 2016 (8)

- June 2016 (10)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (11)

- March 2016 (12)

- February 2016 (10)

- January 2016 (8)

- 2015

- December 2015 (9)

- November 2015 (6)

- October 2015 (8)

- September 2015 (7)

- August 2015 (11)

- July 2015 (7)

- June 2015 (5)

- May 2015 (7)

- April 2015 (8)

- March 2015 (8)

- February 2015 (9)

- January 2015 (10)

- 2014

- December 2014 (12)

- November 2014 (7)

- October 2014 (11)

- September 2014 (10)

- August 2014 (9)

- July 2014 (12)

- June 2014 (9)

- May 2014 (12)

- April 2014 (9)

- March 2014 (6)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (26)